Friends,

As we approach the end of the year and think about what’s to come, we’re forced to reimagine our future in a time of unknowns. I’ve always been a big fan of strategic planning—looking ahead and charting a course gives me a clear sense of purpose and direction. It helps guide me in mission-based decisions and prevents reactive responses that don’t always produce the desired results. In a moment where scientific expertise and human compassion are being challenged, time is critical and we can’t wait for a better political climate to respond. The risk of a “wait-and-see” strategy is that many of our grantee partners may not survive.

We are living in a time where we must reimagine what sustainability looks like. From small grassroot efforts to large academic institutions, in laboratories and adaptive sports clinics, we’ve spent decades building a nonprofit infrastructure that fuels our work and advances our shared values. We broadened our view of the Craig H. Neilsen Foundation’s role in supporting this community; while assuming federal funding would remain the backbone in sustaining research, education, and healthcare, as well as serving as the voice for equity. That approach has led us to make more multi-year programmatic grants, support research that celebrates creativity, and champion mentorship and leadership development—all serving to position issues related to spinal cord injury to be more competitive in obtaining federal, state, and other support.

Well, you know the adage about what happens when we “assume.” Like it or not, this structure is crumbling around us. How we got here is a conversation for another day. What matters now is what we do about it. What proactive steps will develop new models of sustainability? Researchers can’t innovate if they are in constant crisis mode. Nonprofit leaders won’t be able to nurture their organizations if their base of support disappears and the need for capacity building isn’t prioritized. The Neilsen Foundation has begun to shift in response to the changing environment—acknowledging that nonprofits need unrestricted funding and making annual grants at levels above the IRS required minimum distribution of 5% for private foundations.

Philanthropy, no matter how large a foundation might be, can’t take the place of federal funding. The need is just too great. At this critical moment, our role is to find strategic ways to help our grantee partners through this unexpected systemic shift, to help them build the muscle they need to thrive in a post-federal landscape. We need to accept the fact that this is not a temporary fix or something we can wait out; it will have to be a permanent change in how we do business.

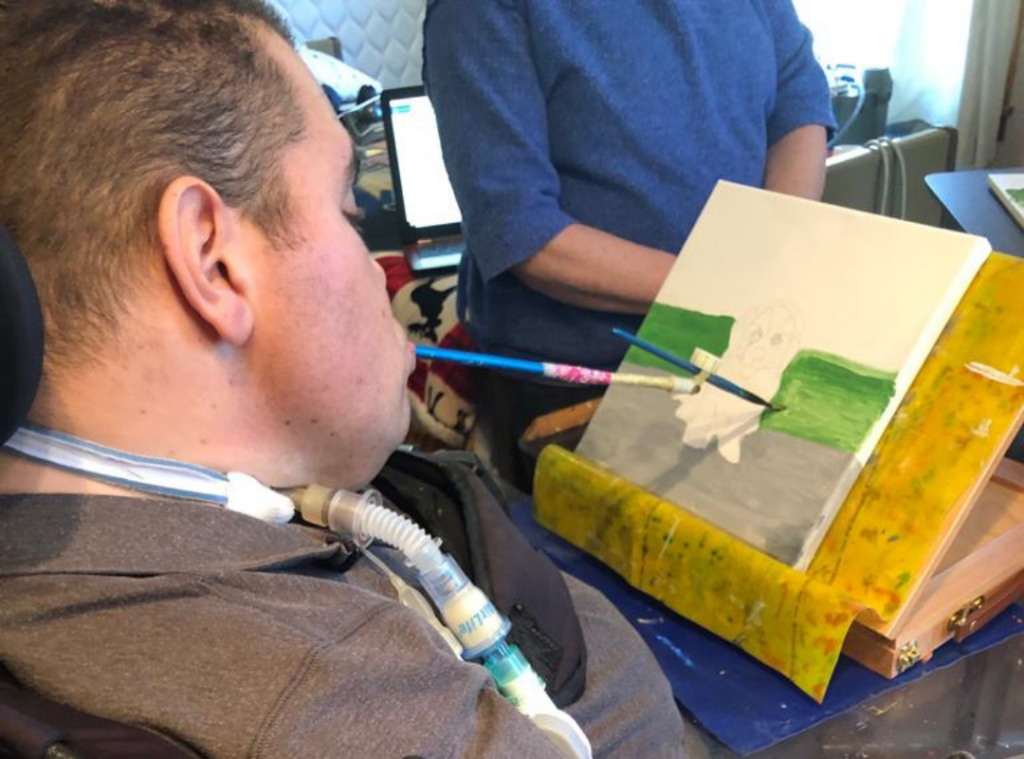

We must think about the decline in federal funding beyond the fiscal challenge and see it as a call to action. Now is the time to lead with innovation, not hesitation. Rather than waiting for more favorable government leadership, a luxury we can’t afford, our communities must commit to taking immediate steps to address the challenges posed. The needs of our communities are not going away, and if we pit one dire need against another, no one will win in the end. A pivotal part of this transformation will be embracing partnerships. Collaboration between researchers, nonprofits, and funders that includes the voice of people with lived experience, is essential in shaping a sustainable future. As we create new funding strategies, we must continue to value inclusion, adaptability, creativity, and a willingness to challenge the status quo. These values, which were modeled by our Founder, will also shape Voices from the Community, a new segment of our eBlasts coming in 2026 designed to elevate perspectives from people across the world of SCI.

I encourage you to think about something you can do to help move us in this direction. Everyone must participate. It doesn’t matter how big or small your idea is—what we need is the collective determination to keep moving forward. Imagine what’s possible.

Be well and happy holidays,

Kym Eisner, Executive Director